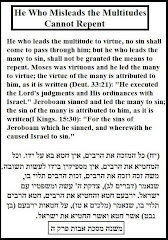

I remember my days at The University Of Virginia, and the Hillel which was lead by a “reform” leader. Days of sitting in non-kosher restaurants with my NBJ (Natural Born Jews) friends while we ate treif and they philosophized about their Jewishness and then decided that they weren’t ready to “go up” to observance. I would subsequently ask myself, in the following decade, how is was that they were so comfortable being “Jew” but transgressing the very Torah that made Jews the Chosen People. The following article sheds light on how this process takes place.

I remember my days at The University Of Virginia, and the Hillel which was lead by a “reform” leader. Days of sitting in non-kosher restaurants with my NBJ (Natural Born Jews) friends while we ate treif and they philosophized about their Jewishness and then decided that they weren’t ready to “go up” to observance. I would subsequently ask myself, in the following decade, how is was that they were so comfortable being “Jew” but transgressing the very Torah that made Jews the Chosen People. The following article sheds light on how this process takes place.It is profoundly troubling that the kind of non-observant Jews whom I met there are still being bombarded by the leaders of heretic “Jewish” movements. Here, Professor Vanessa Ochs, a real-life “Rabbi Brenda,” teaches her brand of Judianity to unsuspecting, innocent, and Torah-ignorant Jewish youth. The author states:

A recent study of young adults in the U.S. has established that “for many students Judaism is more of a cultural issue than a question of religious identity.

Shouldn’t we question the Seinfelding of Judaism?

Last update – 00:00 22/01/2008

Create-as-you-go rituals abound in the U.S.

By Shmuel Rosner

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA

The original plan was to go see the mezuzah, but Professor Vanessa Ochs explained it was removed from the doorpost long ago. It’s probably on a shelf somewhere, gathering dust. Anyway, what’s there to see? Nothing but a brown envelope. Better sit around instead and drink beer.

It was an odd November evening on bustling University Avenue, which looks onto the University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson. Students in gym shorts were taking advantage of the unexpected sun and jogging. Professor Ochs, sitting in a dimly lit bistro, recalled the story of the mezuzah, on which she elaborated in the preface to her recently published book, “Inventing Jewish Ritual: New American Traditions.”

When she and her husband Peter moved to Charlottesville, they wanted to have a mezuzah-hanging ceremony that would also mean something to their non-Jewish friends. This is how the Ochs’ “interactive mezuzah” came about. Basic interactive mezuzah instructions: Hang a traditional mezuzah, ask the participants in the ceremony to write down wishes or greetings on a piece of paper, roll up the paper and insert it in an envelope to be posted on the door beneath the traditional mezuzah.

Girl with a skull cap

Annie Bess sits in the balcony of her peaceful New Haven, Connecticut home, a skull cap on her head and a book in hand. She is a serious-looking girl who tries to avoid defining who or what she considers herself to be. Still, if pressed, she would say that Judaism is very important for her, and for her family, too.

She is an opinionated girl. More specifically, she passes judgment on people who cover their heads in synagogue but not on the street. To her, they’re missing the whole point. Does her mother know? “She’s right here,” Bess says. Her mother is indeed there, her head uncovered.

One can read about Bess and how she became avid in religious observance in Mark Oppenheimer’s “Thirteen and a Day: The Bar and Bat Mitzvah Across America.” Annie Bess is one of the book’s protagonists, as is her next-door neighbor. “There aren’t many 12-year-olds who can talk about their bat mitzvah as she can,” Oppenheimer recounts. “There are a lot of teens who find their bar mitzvah meaningful, but only a few know how to fully articulate its significance.”

Annie Bess’ Judaism is constantly evolving, she says. For example, she had a small crisis with her tzitzit (the fringes on the end of the Jewish prayer shawl). First she wore it, then grew uncomfortable and took it off. “I’m used to wearing a skull cap,” she explains, “but with the tzitzit I felt like I needed support.” Not only support, but also skillful labor since the only tzitzit she could find was designed for boys and “didn’t suit a feminine figure.” Therefore, when she decided to resume wearing the tzitzit, she found herself laboring with the design-measuring, cutting, sowing and tying the four fringes together.

Prayer shawls for women

Hand-made prayer shawls (talitot) for women, writes Ochs in her book, is yet another innovation contemporary Jewish women have made in their religious practice. The Judaica industry quickly caught on and started manufacturing the shawls commercially. But the hand-made shawl did not disappear, just as many male rabbis tend to wear custom-made talitot.

Among women who make their own prayer shawls, a new ceremony has started to gain ground upon completion of the task. Some have made this ceremony part of the bar/bat mitzvah. Here’s how it goes: The birthday boy/girl convenes relatives, covers them in the prayer shawl before it’s been used and receives a blessing. This personal initiation of the talit therefore becomes a familial event.

Torah yoga

Women, who are responsible for most of these innovations, have revolutionized the talit market. Ochs, a religious studies professor, points to the women’s movement as the force for change in the nature of Jewish ceremonies.

A recent study of young adults in the U.S. has established that “for many students Judaism is more of a cultural issue than a question of religious identity.” The growing numbers of progressive Jewish ceremonies have enabled them to integrate Jewish elements in their daily lives. “A generation described as errant, self-centered and disinterested is, in fact, looking for a meaningful sense of community and involvement, only it is in informal and unconventional ways,” says Rabbi Sharon Brous, the leader of the vibrant Ikar congregation in Los Angeles.

Some new rituals aim at a personal, rather than collective, experience. Torah yoga, for example-combining reading verses with movement-rose to prominence as far back as the 1970s, when Eastern philosophies penetrated the West, and is still alive and kicking in the 21st century. Back then, it was an innovative, somewhat eccentric, activity, and today it is right at the heart of the consensus, and continuing to gain ground. Ochs’ daughter, Elizabeth, brought it to Charlottesville four years ago. In several synagogues around town Torah yoga is an occasional substitute for the traditional prayer or Torah sermon.

Across America, Jews are in the process of adopting hundreds of new rituals and trends. In her book, Ochs lists a few dozen: from ceremonies for birth and burial, festivals and rosh hodesh, honoring one’s Christian neighbor, and Holocaust memorial day, to many women-centered ceremonies: condolences for miscarriage, celebrating the menstrual cycle, Purim ceremonies focusing on Queen Vashti (who defied her husband King Ahasuerus) and celebrating the act of breastfeeding.

Elijah’s cup is not alone

Miriam’s Cup started off as a woman-focused ceremony, but in many households it has become part and parcel of the Seder dinner on Passover eve. In versions of Haggadah (the order of the Seder), it is even displayed like a centuries-old custom. But since it is a “recent addition to the Seder, its use is not fixed,” Tamara Cohen wrote in Ritualwell.com, a Web site dedicated to alternative Jewish rituals. Miriam’s Cup is placed on the Seder table beside the Cup of Elijah. Miriam’s Cup is filled with water. It serves as a symbol of Miriam’s Well, which was the source of water for the Israelites in the desert. The blessing that follows is this: “This is the Cup of Miriam, the cup of living waters. Let us remember the Exodus from Egypt.”

1 comment:

Real power is in Torah!

Post a Comment